Managing Relationship Conflict Part IV: Say What? Communicating Effectively (According to Science)

In the past three posts in our relationship series, we have focused on various aspects of managing relationship conflict: dealing with breakups and divorce, the pitfalls of comparing with others, and helping a partner adaptively manage his or her mental health issues.

In today’s post, I would like to address a reader’s request to learn more about communicating with a partner who has a different communication style. Since I’m not a family or marriage therapist, I took this as an opportunity to read up on the work of some wonderful colleagues who are experts in this area. This post will discuss ways to “diagnose” potential communication problems in your relationship and provide suggestions for improving your communication health.

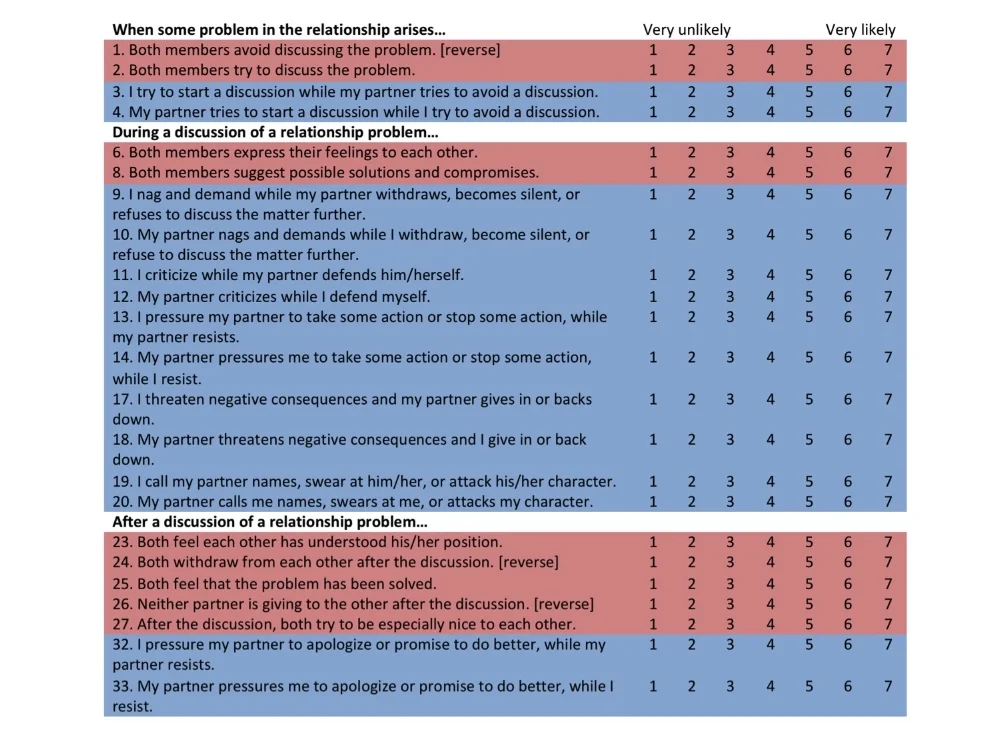

In my literature search, I came across one of the most widely used measures of partner communication styles in large clinical trials of couples therapies, called the Communication Patterns Questionnaire (CPQ; Christensen, 1987; Crenshaw et al., 2017; Schrodt et al., 2014). Trust me, this is not another Cosmo quiz to find out how bad you or your partner are at communicating, so go ahead and take a few minutes to respond to the following items about how you and your partner typically deal with problems in your relationship: (Note that this is not the full measure, and was modified based on the 2017 validation study showing these items are most reliable.)

The red highlighted rows reflect Constructive Communication items, and the blue highlighted rows reflect Self-Demand/Partner-Withdraw and Partner-Demand/Self-Withdraw items.

Some of the red highlighted items are reverse scored, but once reversed, they still contribute to the overall concept of communicating constructively. Constructive communication refers to a set of positive behaviors that promote a collaborative problem-solving approach to relationship issues that supports trust and understanding. In contrast, demand/withdraw behaviors are a set of behaviors in which one partner nags and criticizes the other, whereas the other partner avoids and withdraws from the interaction.

As you might expect, constructive communication has been associated with marital satisfaction and positive relationship outcomes, whereas demand/withdrawal has been associated with greater marital distress, divorce, and infidelity (Crenshaw et al., 2017). In this study, the authors compared communication patterns among 4 samples of couples (for a total of 605 couples!) and found that these items were most reliable across all samples. One of the major takeaways I got from this study was that communicating well falls on a continuum—all partners do some of the red rows and some of the blue rows. But it doesn’t matter if your partner is the one communicating poorly, or if you perceive that you are communicating well. Any combination of one person demanding and the other person withdrawing is just not a healthy pattern.

Communication requires both parties to be on the same page, and that might mean learning to meet your partner where they are at. Here are some other things I have noticed in my clinical work about partners who communicate well:

Good couples have empathy for one another.

Empathy means being able to put yourself in your partner’s shoes and understand how they are feeling or thinking in a certain situation. Part of being good at communicating means being able to understand the concerns and needs of another, especially if they are different from your own.

Sometimes this applies to understanding your partner’s worldview. If your partner grew up in an environment in which parental fighting was taboo and never happened, he or she might develop ideas that fighting is bad. Others might grow up in a family in which fighting was a sign of healthy debate and building a stronger relationship, so they might develop beliefs that not fighting is a bad sign. The key is to remember that fighting itself has been shown to be helpful for relationship growth, so long as the arguments are productive and fair.

Good couples are good at identifying their own feelings.

Aside from being empathic, good communication seems to also involve being able to accurately identify how you are feeling yourself. This starts with being able to identify when you experience basic emotions: happy, sad, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust. With better emotion recognition skills, this means being able to distinguish between more complex emotions, like guilt or shame, or being able to understand the underlying reasons why you might feel angry toward your partner. Building emotion recognition skills always starts with an awareness of your present moment experience.

Good couples say what they mean, and mean what they say.

They leave no room for ambiguity or interpretation, reflect on what’s really bothering them, and convey that in a non-confrontational way to their partner.

Good couples share their experiences with one another.

They talk about minor, insignificant aspects of their day, including positive moments. This is supported by research showing that words aren’t necessary to have shared experiences (Boothby et al., 2014)- just doing something together can be an important step toward improving a relationship.

Good couples understand their respective attachment needs.

A few posts ago, I referred to some nuggets from the attachment science literature, which has shown why individuals with avoidant attachment styles tend not to match well with those with anxious attachment styles. The reason is that people with anxious attachment styles worry that their partners will not reciprocate their love, whereas people with avoidant attachment styles worry about losing their autonomy in relationships.

If you are aware that you tend to be hypersensitive to any sign of rejection or abandonment (anxious attachment), you can communicate this to your partner, in the same way that you can communicate to your partner if you tend to feel uncomfortable being too close in relationships (avoidant attachment). For further reading about the role of attachment in your relationships, see:

References

- Christensen, A. (1987). Detection of conflict patterns in couples. In K. Hahlweg & M. J. Goldstein (Eds.), Understanding major mental disorder: The contribution of family interaction research (pp. 250-265). New York, NY: Family Process Press.

- Crenshaw, A. O., Christensen, A., Baucom, D. H., Epstein, N. B., & Baucom, B. R. W (2017). Revised scoring and improved reliability for the Communication Patterns Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 29, 913-925.

- Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., & Shimkowski, J. R. (2014). A meta-analytical review of the demand/withdraw pattern of interaction and its association with individual, relational, and communicative outcomes. Communication Monographs, 81, 28-58.

- Boothby, E. J., Clark, M. S., & Bargh, J. A. (2014). Shared experiences are amplified. Psychological Science, 25, 2209-2216

By Angela Fang, Ph.D. - Expert Psychologist